By Julie Beth Lake, Ph.D.

Julie Lake is the inaugural Director of the J.D. Legal English Program at Georgetown University Law Center. She relies on her background in linguistics and language-education pedagogy to help multilingual law students navigate the linguistic demands of law school. In this piece, she write about how she has incorporated strategies from Raise the Room into her students. Learn more about Julie at: https://www.law.georgetown.edu/faculty/julie-b-lake/ and https://juliebethlake.wordpress.com/

I. Introduction

I work with multilingual J.D. (law) students at Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, D.C. This past semester, Yuan, a student whose dominant language is Chinese, came to my office hours to discuss strategies to enhance her communication skills. She explained that she gets nervous when her professors ask her questions in her law classes. Her heart starts pumping, and she cannot find the right words. Then, she starts to notice grammatical errors in her speech that she can normally avoid. When she finishes her answer, she ruminates on what she could have done better and wonders whether she even belongs in law school. Yuan was describing the common experience of feeling marginalized in the classroom – and her law school experience – due to her language background. She admitted at the end of our conversation that she worries that her professors perceive her as less intelligent based on her language skills. Yuan, like many multilingual students, described feeling disempowered, uncertain, and, ultimately, voiceless in law school.

To support multilingual J.D. students during their tenure in law school, we started the J.D. Legal English Program at Georgetown University Law Center. When multilingual students begin their J.D. program, they enter into a largely monolingual English environment that has specific, but largely implicit, expectations. I offer a variety of programming to demystify (and push against) these expectations and help students navigate (and thrive in) law school. The programming includes:

- The Oral Communication in the Law workshop series helps increase interviewing, networking, and discussion skills so students can successfully navigate events in and out of the classroom.

- The professional networking meetings create a space for students to discuss their student experiences, learn about resources on and off campus, and build community.

- The one-on-one sessions allow students to work individually on specific skills by determining and addressing their own individual goals for language-related or other issues.

My primary goal is to show multilingual law students that they are an asset to the law school and, by doing so, elevate their voices in the law school classroom. In this post, I highlight two strategies that I use from Meyers’s Raise the Room: A Practical Guide to Participant-Centered Facilitation to (1) center the voices of multilingual J.D. students in law school and (2) increase their confidence. I use these strategies in the workshop series and the professional networking meetings described above.

II. Strategies from Raise the Room: A Practical Guide to Participant-Centered Facilitation

1. Create Group Agreements: Center Participant Voices

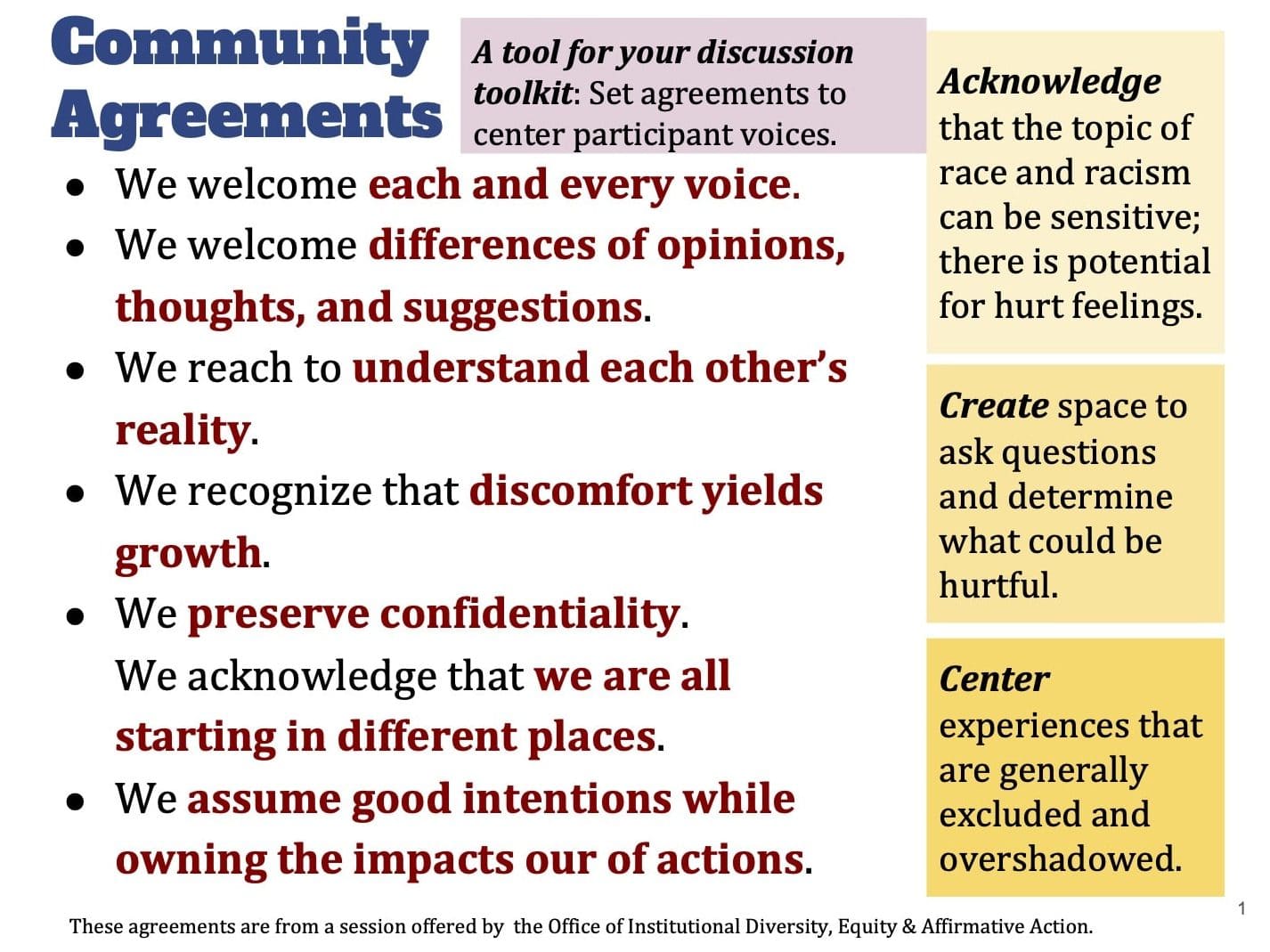

The first technique, which puts participant voices at the center of the conversation, is to create group agreements (see Chapter 22, “Create Group Agreements”), especially when discussing heated topics, such as race and racism. Multilingual students who have not grown up in a U.S. context often find conversations around race and racism puzzling, and they can feel like outsiders looking in. To help students understand the role that race and racism plays in the U.S. context, I devote a session in the “Oral Communication in the Law” workshop series to this topic. In this race-focused session, group agreements serve two purposes. First, they set the stage for students to have productive dialogue about a sensitive topic. But more importantly, they decenter a predominantly monolingual – and white – perspective found in most law school classrooms. When the space that was previously inhabited is freed up, students see how they can participate in these (and other) discussions. You can see a handout of the agreements that I use below; they are adapted from Georgetown University’s Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, & Affirmative Action.

By making room to ask questions, determine what could be hurtful, and put the experiences of participants that are often excluded in the center, students start to see themselves as being integral to these discussions.

2. Create Individual Roles: Boost Participants’ Self-Confidence

The second technique, which helps increase students’ self-confidence, is to create individual roles for the participants (see Chapter 23, “Create Individual Roles” & Peer Coaching Think Sheet) during interactive activities in the larger-group sessions. I will highlight two types of activities that I have found useful: (a) assigning formal roles in interactive activities and (b) offering peer coaching opportunities.

a. Assigning Formal Roles

Let’s start by looking at how assigning formal roles can boost students’ confidence. In law school, multilingual students report that they tend to stay silent during classroom discussions in law school because do are unsure how to participate “appropriately.” Several first-year students have even confided that, over the course of a semester, they have only spoken once or twice, and only when directly called on by their professor. This is striking when we consider that law students are in class for more than 200 hours per semester. As you would expect, this experience tends to feed on itself. Students do not participate in their classes because they are unsure how to do so. The silence leads to a lack of confidence. The lack of confidence leads to more silence. And so on.

To help students feel more comfortable speaking in group settings, I create a space in which students get to try out new roles. The official roles that Meyers recommends include timekeeper, notetaker, facilitator, and dynamic observer. When I put students in small group activities, I usually assign a timekeeper, a notetaker, and a facilitator. This ensures that every student has an opportunity to contribute to the conversation. However, I took the idea of formal roles one step further, and I applied it to the legal discussions in the “Oral Communication in the Law” workshop sessions. Instead of assigning an official role from Meyers’s books (e.g., timekeeper), I give students specific “moves” or “actions” to complete during our formal legal discussions (e.g., ask a question, call for a moment of silence, make a linking comment; see the “Conversational Moves” handout for the complete list of “moves”). When students have a formal role, they have permission to experiment with different ways of interacting in classroom discussions in a low-stakes environment. Over time, students gain confidence and find techniques that work for them in higher-stakes environments, like their law school classes.

After these interactive activities, students tend to relax and participate more freely in future discussions. These formal roles give students the freedom to try out different ways of interacting in a classroom environment.

b. Offering Peer Coaching Opportunities

Now, let’s look at how using peer coaching groups can boosts students’ confidence. I devote a part of each “Professional Networking Meeting” to peer coaching activity pairs. Law school demands that students spend the majority of their time, especially during their first year, reading and thinking. Whether students spend that time in a library, an apartment, or a crowded café, they are spending time alone. This self-imposed isolation can amplify their individual struggles, making them seem unique and insurmountable. In the peer coaching groups, students have the opportunity to listen to each other and ask open-ended questions to help clarify a problem and find a suitable solution. Students in the “coaching” role see that their experience is not unique, which is often a welcome relief, and students in the “coached” role are empowered to find solutions to their own problems with an invested listener.

After listening to their colleagues, students report that they feel not only more connected and but more confident to manage the different stresses of law school.

III. Conclusion

To sum up, I hope that this post has shown you how Meyers’s techniques can boost participant voices by helping multilingual students see themselves as central to the discussions and activities in law school and increasing their self-confidence.